If you’ve been following the news lately, you’ll see headlines stating that Canada’s population grew faster in 2023 than any time since the 1950s (Serebrin, 2024).

Some of the growth is due to immigration. Indeed, immigration is a cornerstone of our history, economy, and commitment to diversity and multiculturalism. However, population changes go beyond international migration and refugees and include natural changes in population (i.e., the difference between birth and death rates of persons already residing in Canada). Over the past 20 years, Canada has seen its population increase around 1-2 percent each year.

However, in 2023, the population increased by around 3 percent.

Canada has experienced short-term population boosts before. In the mid-1940s, the post-war baby boom increased Canada’s population. However, the spread of short-term population boosts is not uniform across the country. Some jurisdictions will experience more growth than others, straining local service providers. For example, starting in the early 2000s, oil and gas developments increased in Alberta. These developments increased the local populations, which increased officer workloads considerably (Ruddell & Ray, 2018).

Furthermore, natural disasters such as the 2023 forest fires near Yellowknife, Northwest Territories resulted in a mass exodus of community residents to safer locations.

Short-term spikes in population place additional stress on government services that, in some cases, were already struggling before new residents came to town. For example, public schools and hospitals are often at or near capacity as they operate within the constraints of the tax base. In rural and remote locations, the situation is likely to be even more problematic.

Policing systems have been systemically under-resourced in the far North (Griffiths, 2019). Thus, a 3 percent increase has the potential to be significant for Canada as a whole, but arguably more stressful in pockets of Canada that are already struggling to service their communities.

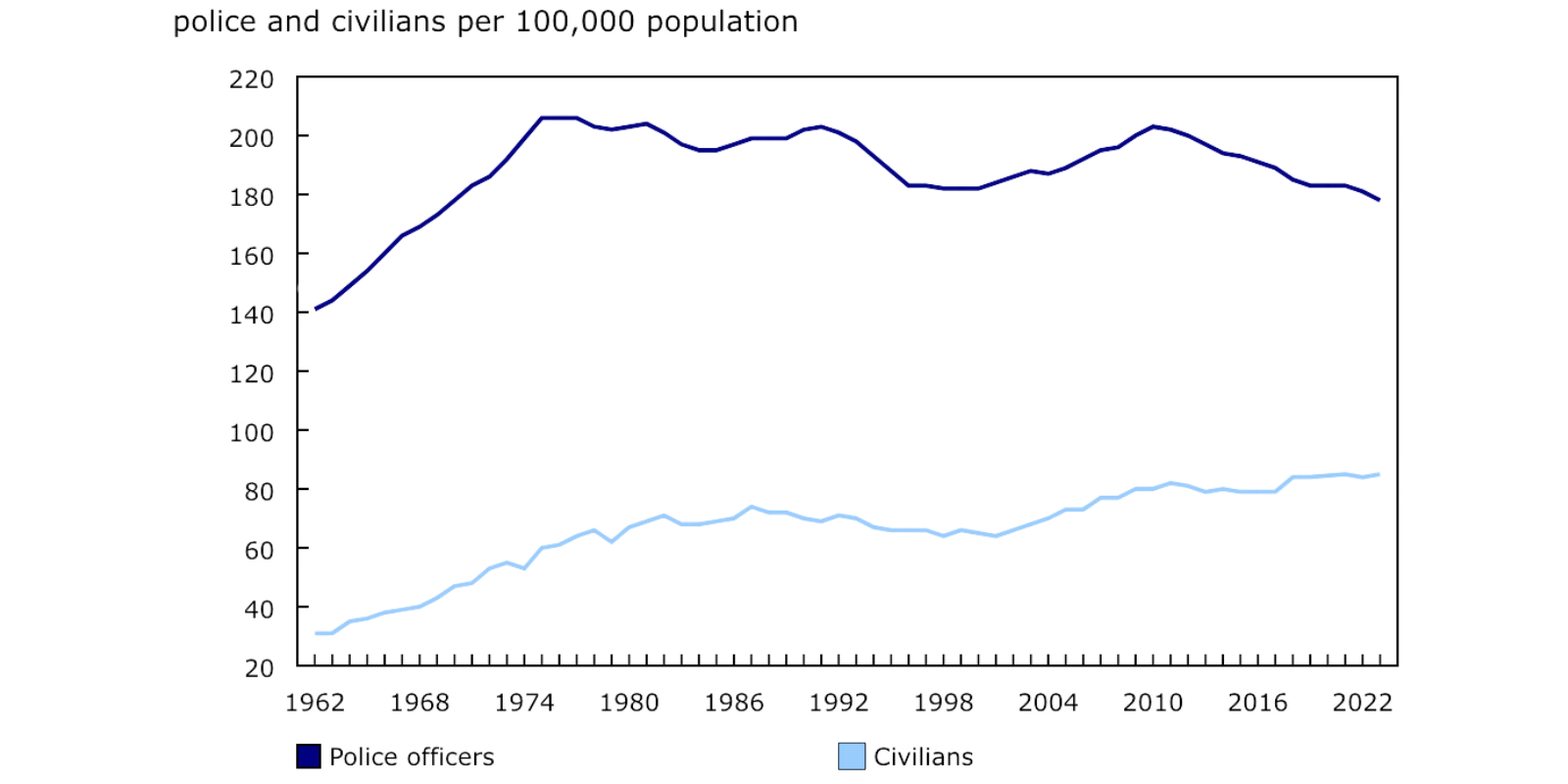

When it comes to comparing population trends with police services in Canada, an interesting pattern emerges. Canada’s police strength was just over 71,000 sworn members in 2023 (Statistics Canada, 2024). As seen in in the dark blue line in Figure 1, this raw count equates to roughly 178 police officers per 100,000 residents (this measurement is informally known as “cop to pop”).

Figure 1 cross-tabulates the ratio of personnel per 100,000 population (the vertical axis) with the year (the horizontal axis).

Figure 1: Rate of police officers and civilian personnel per 100,000 population, Canada, 1962–2023 (Statistics Canada, 2024)

Using cop to pop ratios improves our ability to compare groups of police services. For example, the US with its 330 million residents has approximately 800,000 police officers, or a cop to pop ratio of 240 (per 100,000 people).

In 2010, Canada’s cop to pop ratio was around 203, but this ratio has been steadily declining. An important note here: even though the cop to pop ratio has been decreasing over time, the raw counts of police officers has increased. What does this mean? This means that the population of Canada (or, the denominator in the ratio calculation) is growing at a faster rate than the number of police officers.

You may have noticed that the cop to pop ratio spiked considerably between the 1960s and the early 1980s. There are several factors that drove up the demand for policing during this time, including a surge in crime rates—especially property crimes (Statistics Canada, 2021) —and changes in drug policy (Jensen & Gerber, 1993).

The light blue line in Figure 1 highlights the ratio of civilian staff per population. Civilians working in a policing context are counted differently from sworn/uniform police officers as they perform different tasks within a police service. Sworn police officers conduct patrols and enforce laws, whereas civilians provide an array of support services ranging from administrative support, communications, information technology, and community engagement activities. As shown in Figure 1, the ratio of civilian staff per population has been increasing since the early 2000s. With a ratio of 85 civilian staff per 100,000 residents, 2023 was the highest ratio of civilians working in Canadian policing contexts.

A trend of this nature is good for those of you who may be looking for future jobs or volunteer opportunities in administrative support, communications, information technology, and community engagement activities within the policing context.

The following three questions provide an opportunity for group discussion. Alternatively, you can work through these questions on your own.

Discussion Questions

-

In this blog post, the impact on acute population growth has been discussed in the context of police services. Are there other aspects of your daily life that you think could be impacted by rapid population growth? Do any of these areas intersect with the typical duties for police officers? To get started, you might want to think about housing and traffic.

-

As noted above, the pop to cop ratio has been declining since 2010. What are your thoughts about this 10-year downward trend? Have you noticed that there are relatively fewer police officers in your city or municipality? What should be done (if anything) to prevent the ratios from declining even further? Alternatively, do you think we should increase our ratios to mirror those in the United States? Why do you feel this way?

-

Why do you think the ratios of civilians and sworn police officers per 100,000 residents are seemingly going in opposite directions? To help you answer this question, refer to https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/rsrcs/pblctns/2015-r042/2015-r042-en.pdf.

References

Griffiths, C. T. (2019). Policing and community safety in northern Canadian communities: challenges and opportunities for crime prevention. Crime Prevention and Community Safety, 21(3), 246-266. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41300-019-00069-3

Jensen, E. L., & Gerber, J. (1993). State efforts to construct a social problem: The 1986 war on drugs in Canada. The Canadian Journal of Sociology, 18(4), 453-462. https://doi.org/10.2307/3340900

Kiedrowski, J. S., Melchers, R. F., Ruddell, R., & Petrunik, M. (2017). The civilianization of police in Canada. Public Safety Canada. https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/rsrcs/pblctns/2015-r042/2015-r042-en.pdf

Ruddell, R., & Ray, H. A. (2018). Profiling the life course of resource-based boomtowns: A key step in crime prevention. Journal of Community Safety and Well-Being, 3(2), 38–42. https://doi.org/10.35502/jcswb.78

Serebrin, J. (2024). Statistics Canada says population growth rate in 2023 was highest since 1957. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/population-growth-canada-2023-1.7157233

Statistics Canada (2021). Police-reported crime rates, Canada, 1962 to 2020. July 27, 2021. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/210727/cg-a002-png-eng.htm

Statistics Canada (2024). Police resources in Canada, 2023. The Daily, March 26, 2024. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/240326/dq240326a-eng.htm

Written by: Adam Vaughan